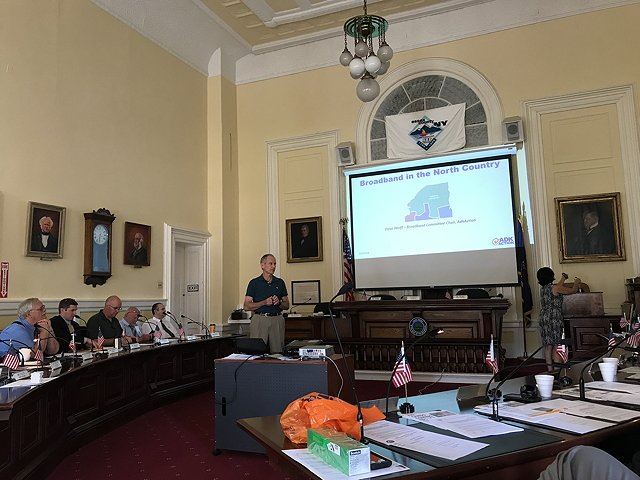

David Wolff, broadband committee chair of AdkAction, briefs the Essex County Board of Supervisors on broadband updates on Sept. 4, 2018.

Photo by Pete DeMola

ELIZABETHTOWN

A nonprofit has stepped forward to serve as a conduit between local government and the state agency overseeing the broadband build-out effort.

AdkAction Broadband Committee Chair David Wolff attempted to lasso in lawmaker concerns during a presentation to the Essex County Board of Supervisors last week.

Wolff said he has been in contact with the state Broadband Program Office (BPO), the office overseeing the state’s universal broadband build-out, and will relay local concerns up the food chain.

“What information would you like to see to help you manage the rollout of the program?” Wolff asked lawmakers. “How can we streamline that process?”

POINT PERSON NEEDED

Wolff urged the Essex County Board of Supervisors to appoint a designee at the county level who can help local officials navigate bureaucratic hurdles in Albany.

Doing so, he said, may be more effective than individual lawmakers contacting the BPO with their concerns.

The program has steered $154 million in subsidies to boost high-speed internet in rural North Country communities — the most of any region in the state.

But local officials have long fumed over what they perceive to be a lack of transparency from the BPO, leaving them adrift as they attempt to pin down specific details on build-out projects in their communities.

Lawmakers fret that the BPO has leaned too heavily on U.S. Census maps to award grants and that locations that may fall through the cracks, a viewpoint complicated by the state’s eviction of Charter from the state earlier this summer.

Wolff encouraged lawmakers to pinpoint areas in their communities that may be left unserved once the program concludes at the end of next year.

“We need to identify those households; we need quantify and figure out how big the problem is, and what monies will be required to actually solve and connect those people,” Wolff said. “Until we connect those folk, the governor’s claim of 100 percent coverage is not going to be accurate.”

He asked lawmakers to study the state-crafted maps detailing grant coverage areas at nysbroadband.ny.gov/resources/residential-broadband.

Lawmakers appeared to approve of a Wolff-created map that shows grant awards color-coded by provider in each town — not by the amount of grant awards provided or speed promised.

Since announcing the third and final round of grant funds in January, state officials and providers have participated in a pair of forums in North Creek and Willsboro.

Lawmakers indicated they’d be open to a third session, including Lewis Supervisor Jim Monty, who was disappointed at the lack of a Q&A at a public hearing last month in Elizabethtown.

“If this is your idea of open and transparent government,” wrote Monty in an email to the BPO last week, “I am ashamed to be a part of this.”

The first two phases of the program will be completed by the end of the year, while recipients of the third and final round of funding have until the end of 2019.

“The ball’s in your court,” Wolff told lawmakers. “You at the town level have to manage the rollout. This is a finite time. We’re talking into 2019. After that, then all bets are off.”

LAWMAKERS REACT

Essex County Board of Supervisors Vice Chairman Shaun Gillilland said he welcomed Wolff’s suggestions on how to “repair and improve” the information that is available to local officials about coverage issues.

“I came away with a clearer understanding of the nature of the problem where we sit today,” he said. “Our homework on this is to quickly figure out the scope of the problem. Once we get knowledge of the problem, we will know how tackle it.”

But Gillilland, who also serves as Willsboro supervisor, continues to harbor concerns over the structure of communication with the BPO, providers and local government once build-outs have been completed, as well as how to regulate underperforming providers and the specific points of contact for complaints.

“I know it’s going to fall down to local governments to be able to regulate what’s going on in the town,” said Gillilland, who also expressed concerns that those subscribed to failing legacy systems will not get upgraded.

As part of the program, providers must cap monthly costs at $60 for five years, and are required to provide minimum speeds of 25 mbps in the most rural areas.

But residents have pointed out that providers who have received state subsidies continue to offer sub-par service.

Gov. Andrew Cuomo told reporters in January complaints should be directed to the Public Service Commission (PSC).

UNDERSTANDS FRUSTRATION

Thirty percent of New Yorkers did not have high-speed broadband in 2015, according to the BPO.

Keene Supervisor Joe Pete Wilson said he can’t overstate how important the service is to rural communities, and how critical the state investment is.

That’s why lawmakers are so passionate, he said.

“In our rural towns, not having it — or having limited access to broadband — hurts our economy and hurts our education system,” Wilson said. “I want broadband and am supportive of this program.”

Gillilland, too, acknowledged the state’s commitment.

But the governor has made a promise to his constituents, he said, citing the pomp and circumstance of the program announcement in Lake Placid in 2015.

“It’s between the governor’s office and individual households,” Gillilland said. “It’s very personal. It was promised, and if it doesn’t happen, people are going to be very angry.”

The BPO are aware of Wolff’s presentation, and said they work closely with a number of community organizations and local governments.

“Their insight and feedback has been valuable as we build out broadband across the region, which is receiving over $150 million in public investment that will provide access to more than 47,000 homes,” said Adam Kilduff, an agency spokesman. “The (BPO) is committed to providing access to high-speed internet to all New Yorkers.”

Residents who want to offer feedback on BPO-funded projects can contact the BPO directly at [email protected].

SPECTRUM QUESTION

Another dangling question when it comes to filling high-speed internet gaps in the Adirondacks is the extent of Charter’s involvement.

As part of Charter’s takeover of Time Warner in 2016, the provider was required by the state Public Service Commission (PSC) to extend service to 145,000 underserved locations statewide.

Charter, which conducts business as Spectrum in New York state, and the state Broadband Program Office have acknowledged some of the 145,000 locations are in the North Country. But they’ve long contended that information is private, frustrating local officials who want clarification on which locations in their towns stand to be served.

Adding further ambiguity, the PSC claims Charter hasn’t reached the build-out goals and commenced eviction proceedings in July, leaving officials wondering how the change will affect their communities.

“We need an answer of what is going to happen if they force Spectrum out of Essex County,” said Lewis Supervisor Jim Monty, who estimated a departure would result in 60 percent of his constituents losing service.

Essex County Board of Supervisors Vice Chairman Shaun Gillilland called the ongoing flap a “massive unknown.”

“If it goes south, it’s going to bring this whole state project with it,” Gillilland told The Sun.

Charter, which has disputed the PSC’s claims, has until Oct. 9 to submit an exit plan to the state regulatory agency.

Moriah Supervisor Tom Scozzafava says approximately 90 locations in his community stand to be served by the provider.

“Trying to obtain the information has been very difficult, if not impossible,” said Scozzafava, who contends he has been stonewalled by the PSC, Spectrum and the governor’s office when he’s asked for clarity.

But reversing years of claims by Charter and the BPO stating details on build-out efforts are private, AdkAction Broadband Committee Chairman David Wolff told lawmakers towns have the right to ask for an understanding of the network within their franchise areas, and can obtain that information if they sign a non-disclosure agreement.

“Franklin County has done this at the county level,” Wolff said. “They have gone and signed a non-disclosure with Spectrum.”

Scozzafava called for Spectrum to send a representative to a county board meeting.

“That would be a huge first step,” he said.

By Pete Demola